Haumaka

Great Confederation of Hau Maka | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| File:Haumaka location.png | |||||

| Capital | Mataki | ||||

| Official languages | Haumakan | ||||

| Recognised national languages | Jeongmian | ||||

| Recognised regional languages | Vaiteka | ||||

| Ethnic groups |

XX% Haumakan XX% Vaiteka | ||||

| Demonym(s) | Haumakan | ||||

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy | ||||

| XXX | |||||

| XXX | |||||

| Population | |||||

• 2021 estimate | 5,334,963 | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2021 estimate | ||||

• Total | 圓79.13 billion | ||||

• Per capita | 圓14,833 | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2021 estimate | ||||

• Total | 圓40.77 billion | ||||

• Per capita | 圓7,642 | ||||

| HDI |

high | ||||

| Currency |

Haumaka mamari ( | ||||

| Time zone | UTC+5 | ||||

| Driving side | left | ||||

| ['Iorana! Consider taking a moment to educate yourself about the real-life Rapa Nui people whose culture inspired Haumaka]. |

Haumaka (Haumakan: ![]() , 하우 마가, Hau Maka; Vaiteka: Hamáka; Jeongmian: 장승도, Jangseungdo), officially the Great Confederation of Haumaka (Haumakan:

, 하우 마가, Hau Maka; Vaiteka: Hamáka; Jeongmian: 장승도, Jangseungdo), officially the Great Confederation of Haumaka (Haumakan: ![]() ,Te Hanau Nui a Hau Maka 데 하나우 늬 아 하우 마가; Vaiteka: Hamáka Mókstapwask; Jeongmian: 장승도 대연맹, Jangseungdo Daeyeonmaeng) is a country in the Chehou Islands, west of Cheongju in the Eastern Ocean, and culturally part of Haegye. It consists of three main landmasses - from north to south, the islands of Kainga Nui, which contains the majority of Haumaka's area and population, Kavai (Vaiteka: Ka'wais), and Rekohu - along with a number of smaller islands. Haumaka directly borders Kumucachi by sea.

,Te Hanau Nui a Hau Maka 데 하나우 늬 아 하우 마가; Vaiteka: Hamáka Mókstapwask; Jeongmian: 장승도 대연맹, Jangseungdo Daeyeonmaeng) is a country in the Chehou Islands, west of Cheongju in the Eastern Ocean, and culturally part of Haegye. It consists of three main landmasses - from north to south, the islands of Kainga Nui, which contains the majority of Haumaka's area and population, Kavai (Vaiteka: Ka'wais), and Rekohu - along with a number of smaller islands. Haumaka directly borders Kumucachi by sea.

It is a member of the Congress of Nations and the Jangjip Council, and an observer of the Jeongeogwon Organization.

Etymology[edit]

Hau Maka was originally a personal name, that of the prophet who dreamed the location of the islands and instructed Tu'u ko Iho to find them in the Haumakan founding legend; as a result the first Haegyean settlers named their new home Te Kainga o Hau Maka, "the plot of land of Hau Maka", which was eventually shortened to simply Hau Maka (and usually rendered as one word in other languages). The first part of the original name was preserved in the name of the largest island of Haumaka, Kainga Nui ("big plot of land"), after Haumaka as a whole and Kainga Nui in particular eventually ceased to be seen as synonymous. Other archaic names or poetic names for Haumaka include Mata Ki te Rangi, "eyes toward the sky", and Te Pito o te Henua, "the navel of the world" or "the end of the world".

The original Vaiteka name for Haumaka is unknown, although some historians have suggested that Kawais, the Vaiteka name for Kavai meaning "island of stones", may have originally referred to Kainga Nui or to the archipelago as a whole.

Haumaka's Jeongmian name, 長承島 Jangseungdo, roughly means "totem island" and refers to the moai, which early Jeongmian and Namjuan explorers likened to jangseung.

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

Vaiteka period[edit]

The earliest inhabitants of the islands that now make up Haumaka were the Vaiteka, a Cheongjuan people who arrived in the archipelago perhaps ten thousand years ago. They lived a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle (with the exception of cultivating potato gardens) based out of their traditiona talaka canoes, mostly around the coasts, with the interior only sparsely populated. Some tribes fell under the influence of states in Kumucachi and eventually the Sipan Empire based in Quixmican, trading with them and paying them tribute, but none of those states ever established a firm grasp over Haumaka.

Early Haegyean period[edit]

Between 800 and 1000 CE, a wave of Haegyean settlers arrived in Haumaka. According to Haumakan oral history, they originated from the islands of Hiva, which have usually been associated with Kealakekua, but speculated to also be as far away as Malu'i or possibly a mix of the two. They were able to make this migration, one of the longest recorded in pre-modern history, with the aid of technologically advanced outrigger canoes and sophisticated navigation techniques. Migration and contact between Haumaka and the rest of Haegye ceased after about 1000 CE for unknown reasons.

According to the Haumakan founding legend, the Hivan chieftain Tu'u ko Iho escaped persecution in his native land and sailed to a location that his friend Hau Maka had dreamed with his family in a single canoe. Once there he used magic to cause the first moai to "walk" from the mountains to the shore, which angered the Vaiteka and caused them to attack his people; the Vaiteka were defeated and all killed except for two, who fled to Kavai, and the now-emptied island of Kainga Nui was divided between Tu'u ko Iho's sons, from whom all Haumakans descend. In contrast, archaeological evidence suggests that there were several Haegyean landings in Haumaka rather than just one, that the first moai post-date Haegyean arrival for several centuries, that the island was divided into clan territories only gradually, and that Vaiteka material culture persisted in Kainga Nui for several more centuries. In addition, genetic evidence has demonstrated that most Haumakans have significant Vaiteka admixture rather than being purely Haegyean, suggesting a gradual assimilation of Vaiteka into Haegyean culture.

Though fewer in number, the Haegyeans were more technologically advanced than the Vaiteka, introducing agriculture (taro and yams, in addition to making use of native potatoes) and livestock (chicken and pigs). They were also able to use their more advanced boats to carry out greater trade with the rest of the Chehou Islands, and adopt further technological and agricultural techniques from them, beginning a gradual urbanization (while the native Chehou Islanders adopted their shipbuilding techniques in turn). The Haegyean population grew rapidly over the next few centuries as a result, allowing them to dominate, subjugate, and eventually assimilate the Vaiteka, except for on Kavai. The Haegyeans divided Kainga Nui into eight mata or clan territories during the initial settlement period between 800 and 1000; between 1000 and 1200 the mata coalesced into two hanau or confederations, Hotu in the west and Miru in the east.

Moai-building period[edit]

By 1200, the eastern Miru confederation had grown more powerful from its control of the lucrative trade with the other Chehou Islands and obtained the vassalage of the Hotu confederation (as well as Kavai), establishing a unified kingdom. The royal period from 1200-1500 was a golden age for Haumaka, with a cultural flowering that saw the country’s most celebrated outputs, the erecting of the famous moai statues and the development of rongorongo script, and extensive trade and cultural exchange with the other Chehou Islands. After 1500, the kingdom collapsed into civil war due to overpopulation and competition between clans over resources. Around this time a group of refugees settled the far southern island of Rekohu and adopted a pacifist lifestyle.

Birdman period[edit]

As a result, power devolved from the aristocratic class to the warrior class and a new religious movement emerged to supplant the old religion that had centered around the moai and ancestor worship: the tangata manu or birdman cult, under which resources would be distributed and ritual leadership (the position of “birdman”) assigned to the clan that won an annual ritual race. Over time, the priesthood that administered the birdman ceremony itself gained great power.

Moai-toppling period[edit]

By the 1700s the birdman system also began to fall apart due to renewed tensions between clans and social classes. As part of these internecine conflicts, the slave raids which had always been part of Haumakan warfare intensified and clans began trading the captives to Sinjuan traders, especially Jeongmians who transported the slaves to Namju, in exchange for manufactured goods, especially firearms. More powerful weapons and the economic incentive of slave-trading exacerbated worsening blood feuds between clans that escalated into the Musket Wars, a devastating social collapse that lasted into the 1800s that may have reduced Haumaka's population by as much as half between those taken away as slaves and deaths to war, resulting famine, and introduced diseases. During the Musket Wars, almost all standing moai were toppled by various clans in attempts to damage the mana of rival clans' ancestors, a phenomenon known as the huri mo'ai ("statue-toppling").

Colonial period[edit]

Amidst this internecine conflict, Namjuan slave-traders and other private interests in the Jeongmian Empire formed the Jangseung Company, which steadily formed alliances and protectorates with the various clans until the entire country was under its at least indirect control by the signing of the Treaty of Maheke in 1845, formalizing its control effectively ending the Musket Wars. In the post-treaty era of company rule, rebellions flared up with the goal of restoring the old kingship and reasserting Haumakan sovereignty. By the 1860s, company forces were overwhelmed and the Jeongmian military was called in to suppress the rebels, as a result of which the Jeongmian government confiscated Haumaka from the Jangseung Company and directly annexed it as a colony in 1872.

Under direct rule, the slave trade ended and the colony's economic focus shifted to mining and ranching, though it maintained economic ties with Namju and much of the colonial administration was drawn from there. Many traditional customs like the birdman ritual, rongorongo, and tattooing were banned and suppressed, being seen as responsible for the unrest of the company period. During the Great Eulhae War, Haumaka was a strategic Jeongmian naval bases, and Haumakan troops served in the Jeongmian forces and gained a reputation for bravery.

After Eulhae, an independence movement surged in support, and initially had a strongly socialist orientation due to backing from the nearby socialist state of Kumucachi and eventually Qichwallanqa. Seeing independence as inevitable but seeking to counter the threat of Haumaka becoming a socialist state itself after independence, the colonial authorities reversed their early custom bans and encouraged a cultural revival. Over the course of the 1950s, rongorongo script was restored, birdman rituals resumed, and moai were re-erected.

Independence[edit]

Haumaka became independent in 1962 with the restoration of the old monarchy and clan territories, albeit in modern form as federal provinces and a constitutional monarchy. Rekohu was not included within Haumaka at independence and remained a Jeongmian colony until voting to join Haumaka in 1982. On the other hand, Kavai is home to a long-simmering separatist movement.

Geography[edit]

Administrative divisions[edit]

Haumaka is divided into four hanau, literally "confederations" and the equivalent of regions: Miru and Hotu on the island of Kainga Nui, and the islands of Kavai and Rekohu. Miru and Hotu are further divided into eight mata, the equivalent of districts: Maheke, Aro, Marama, Raa, and Koro in Miru, and Hotu Iti, Tupahotu, and Ngaure in Hotu. Most local administration takes place at the hanau level in Kavai and Rekohu, and at the mata level in Hotu and Miru.

Climate[edit]

Flora and fauna[edit]

The national flower is the Haumakan bellflower and the national tree is the Haumakan cypress, one of the largest and longest-lived species of tree in Tiandi. Further endemic trees include the monkey puzzle tree, the toromiro, the southern beech, the Cheongju mountain bamboo, the maki berry, the temu, and the Haumakan hazel. Other endemic plants include the totora, the akupala, and the giant rhubarb.

The national bird is the sooty tern, considered sacred for its association with the creator god Makemake and its central role in the tangata manu ritual, and the national animal is the southern pudu, the smallest species of deer in Tiandi. Other endemic land mammals include the Chehou fox, the kodkod, the colocolo opossum, the coypu, and the southern river otter. In addition, much of the island now has a large population of wild horses introduced during the colonial era. Species found off the Haumakan coast include the Byeonic penguin, the Cheongju sea lion, the panda dolphin, and the pygmy blue whale.

Government[edit]

Politics[edit]

Foreign relations[edit]

Legal system[edit]

Military[edit]

Economy[edit]

Infrastructure[edit]

Science and technology[edit]

Tourism[edit]

Tourism forms a major part of Haumaka's economy. The largest number of tourists come from Namju, followed by Nambo. The biggest tourist attractions are the moai; other attractions include beach and ski resorts, natural landscapes and adventure tourism, and cultural performances and demonstrations.

Haumaka has six CONESCO World Heritage Sites, a relatively high number for such a small nation: three cultural sites, the two moai sites of Raraku Quarry and the Royal Ahu of Tahai and the "Cultural Landscape of Kavai" with its Vaiteka architecture of stilt houses and wooden temples; two natural sites, the Hotu temperate rainforest and the Subantarctic Islands, and the combined cultural and natural site of Ranomanu Caldera. Of these, the moai sites and Ranomanu receive the most visitors, while the Subantarctic Islands receive fewer visitors due to their remoteness, though they are sometimes visited by nature cruises.

Demographics[edit]

Largest cities[edit]

Ethnicity[edit]

The indigenous ethnic groups of Haumaka are the Haumakans and the Vaiteka. The Haumakans make up a large majority of the national population as a whole and in each subdivision of the country other than Kavai. They are a Haegyean and Jangjip people who migrated from Haegye and settled in Haumaka around 800-1000 CE, and are further subdivided into eight clans and the Maohi of Rekohu, who are sometimes considered to be a distinct ethnic group. Before the colonial era, most Haumakans identified first and foremost with their clans above any shared Haumakan identity. Since independence the reverse has been true, with clan affiliations much weaker than shared Haumakan identity and a high level of intermarriage between clans and movement between clan territories, though most Haumakans still identiffy with a particular clan to some degree. Due to the historic slave trade as well as more recent, mostly economically motivated emigration, there are almost as many ethnic Haumakans living in the Haumakan diaspora, mostly in Namju and Nambo, as there are in Haumaka itself, although not all of these still identify with Haumakan culture.

The Vaiteka are a Cheongjuan people who make up the majority of the population of Kavai island, with smaller populations in the rest of the country, mostly in urban centers. Their presence predates that of ethnic Haumakans, having arrived around 10,000 years before present. The Vaiteka relationship with the ethnic Haumakan majority has historically been ambivalent and shifting, with periods of autonomy alternating with periods of subjugation. Since independence many Vaiteka have felt alienated by the government's nationalistic emphasis on ethnic Haumakan culture and by Kavai's economic and political marginalization relative to Kainga Nui, in turn fueling Vaiteka nationalism and the Kavai sovereignty movement as a reaction. In addition to the two indigenous ethnicities, Haumaka is also home to a small number of Sinjuans, mostly ethnic Jeongmians (including Namjuans) either left over from the colonial era or living in the country for work as expatriates, and of immigrants from other countries in Cheongju, especially Kumucachi and Quixmican.

Language[edit]

The official language of the country is the Haumakan language (Vaananga Hau Maka), a member of the Haegyean branch of the Jangjip language family closely related to Kealakekuan and Mallinese. The vast majority of the population can speak and understand Haumakan. The Vaiteka language (Wayteka Wurkwurwe), a language isolate speculated by some linguists to be related to the Yikyarikan and possibly Marakwian languages of Wirchulich, was the original language spoken in Haumaka before the Haegyean settlement and currently has co-official status with Haumakan on the island of Kavai, where ethnic Vaiteka make up a majority. Many linguists consider the Rekohu dialect to be divergent enough from standard Haumakan to be considered a separate language, and some activists on Rekohu have advocated for the government to recognize it as such, but it currently does not have any official status. Jeongmian is widely spoken as a second language, especially in urban and touristic areas, as a legacy of Namjuan colonialism and continued influence and economic ties, and has an intermediate status as recognized at the national level but not official. Haumaka is a full member of the Jangjip Council for Jangjip-speaking nations, and an observer of the Jeongeogwon Organization for Jeongmian-speaking nations.

Both Haumakan and Vaiteka use the rongorongo syllabary, a script native to Haumaka and developed there around the 15th century in what may have been one of the few independent inventions of writing in human history. During the colonial era, rongorongo was suppressed and Haumakan was written in Jeongja; after independence the use of rongorongo was restored and the previously uncodified script was standardized for the first time and simplified to its current 52 characters. Rongorongo spread from Haumaka to the rest of the Chehou Islands and is also used by other languages including Jollana Miñ in Kumucachi and Quixmic in Quixmican.

Religion[edit]

In pre-colonial times, the two native religious traditions, the earlier mo'ai ancestor-worship cult and the later tangata manu birdman cult, were considered to be distinct religions and even at odds with each other. However, since a late-colonial revival of the previously-diminished ancestor cult, they have usually been practiced together and considered to be two parts of a single national religion.

Education[edit]

Health[edit]

Culture[edit]

Art[edit]

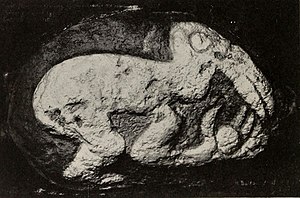

The most famous symbols of Haumakan culture, and indeed the thing which the country is perhaps most famous for world-wide, are the mo'ai (lit. "statues"), monolithic statues carved from volcanic rock into the shape of human figures. They vary in size and height, with the tallest ranging up to ten meters and the heaviest ranging up to eighty tons, with unfinished examples having been unearthed that would have been even larger and taller if completed. The moai have oversized, elongated heads with stylized features making up nearly half of their length, and appearing to be even more in the cases of statues partially buried up to the shoulders, leading them to often but inaccurately be called "Haumakan heads". In reality, they are carved up from the thighs (except for a few rare examples with full legs, portrayed kneeling), with arms carved into them in bas-relief and often with petroglyphic designs etched into their backs, though many of these have eroded over time. Many moai have or had pukao capstones carved from red scoria, representing hair, and white coral eyes with black obsidian pupils.

The moai were placed on ahu, stone platforms that served as sacred sites, usually along the shore and facing inland. They represented... Most moai were toppled during the huri mo'ai or "statue-toppling" of the civil wars of the 18th and 19th centuries, but many were re-erected with great ceremony after independence.

In addition to the more famous stone-carving tradition, Haumaka also has a rich wood-carving sculptural and artistic tradition, with forms including the reimiro, a crescent-shaped ceremonial breastplate with human faces carved at the ends, and the mo'ai kavakava ("emaciated statues"), grotesque and highly detailed elongated human figures representing ancestors made to be worn around the neck or danced with like dolls during ceremonies.

Architecture[edit]

Haumaka shares with many other Jangjip peoples the namesake trait of building stilt houses, in the Haumakan case built above water; during the colonial era they began to be painted in their now-characteristic bright colors.

Cuisine[edit]

Haumakan cuisine is a combination of Cheongjuan, Haegyean, and Sinjuan influences. Ingredients native to Haumaka and used by the Vaiteka include shellfish... and most notably an abundance of native potato varieties, made in a number of preparations including milakao pancakes, kapalele dumplings, and rēvena bread made from fermented potatoes. The Haegyeans introduced chicken, pork, sweet potato, taro...

The most traditional style of preparing food is umu, in which meat, shellfish, potatoes or sweet potatoes (whole or as milakao or kapalele}, and various other vegetables are all cooked together in an earth oven and eaten together as a stew. Pulumai is similar to umu, but boiled in a broth in a pot rather than cooked dry in an earth oven. Seafood dishes are also common, including tunu ahi, fish grilled on rocks, and 'ota 'ika, raw fish marinated in citrus juice to cure it, similar to Cheongjuan siwichi. A popular dessert is po'e, a mashed and baked taro pudding. Condiments include merukengi, smoked chili peppers, and... Beverages include 'ti'ta, made either fermented or unfermented from various fruits and starches, and since the colonial era, una'i, an ugniberry liqueur.

Dance[edit]

The hoko is a group dance with accompanying chanting that was traditionally performed by warriors before battle, and is still performed at special occasions such as weddings and funerals, to welcome dignitaries, and most famously by Haumakan sports teams ahead of matches.

Drama[edit]

Fashion[edit]

Like other Jangjip peoples, Haumakans practice tattooing, referred to as ta kona in Haumakan. Tattoos are placed on the face, hands, arms, legs, and buttocks by both men and women in a variety of geometric, zoomorphic, and anthropomorphic designs, many with religious meanings; the most common design is lines across the forehead. Traditionally tattoos were applied using needles and combs made from bird or fish bones and ink made from burned leaves, but today more modern tools and materials are often used. Haumakans tattoos have spiritual significance as they are considered to be receptors of mana, or spiritual energy and strength. Historically tattoos were used to indicate social status, both through specific designs and the overall amount of tattoos, with the upper classes having more tattoos and priests having the most of all, but today this is less prevalent and tattoos generally no longer correlate to class. Tattooing was banned for much of the colonial era but revived as a symbol of national pride after independence.

Film[edit]

Holidays[edit]

The Haumakan calendar is lunar and divided into thirteen months. Its two main traditional holidays are Matariki and Tapati. Matariki, the Haumakan new year, is celebrated with the first heliacal rising of the Pleiades, roughly coinciding with the southern hemisphere's winter solstice, and is also considered to mark the anniversary of the Haegyean discovery of Haumaka. Tapati Tangata Manu, the Birdman Festival, often simply referred to as "Tapati", is a weeklong celebration of traditional sports, music, and dance held in the summer, aligning with the local breeding season of the sooty tern and roughly coinciding with the Sinjuan new year. In modern times, Independence Day is also a major holiday.

Literature[edit]

Media[edit]

Music[edit]

Sports[edit]

For centuries the Tangata manu ("birdman") race was central to Haumakan religion and politics, being used to determine leadership within and between clans. Both a sporting competition and a religious ritual, competitors would race to swim across a channel to an islet or outcropping where terns nested, collect the first tern egg, swim back across, and climb up a cliff to the ritual site; the winner would be named the "birdman" and his clan would receive leadership over the others for the next year. Tangata manu ceased to be practiced during the colonial era but has been revived since independence as a cornerstone of national history and identity, although while it still has religious significance in honoring the creator god Makemake, its political role has ceased, and an artificial tern egg or other symbolic ball is almost always used instead of a real egg as terns are now a protected species.

Other traditional sports include haka pei, a form of snowless sledding in which tree trunks are tied together and ridden down a steep hillside (often considered an extreme sport, where injuries are frequent), vaka hurdling, and cliff diving. As in many other Haegyean nations, the most popular spectator sport is rugby.